MANCHESTER, NH – Knowledge became power for West High School senior Jacob Plamondon. He says the opportunity to examine his spending habits as part of a financial literacy course designed by the National Collaborative for Digital Equity (NCDE) was a revelation.

“For me, the biggest mistake I made was buying food,” says Plamondon, 18, one of 19 students from the West who took part in the course which ended on April 15. Now that he has his eyes opened, one of the changes he has made is to control his restaurant food spending. He now puts at least $50 of every paycheck he receives from working at Rite Aid in a savings account and tries to buy food more often than he can prepare at home.

So far he has used some of his savings to buy a car, with help from his parents, and is enjoying what he has learned during the intensive seven-week course. School principal Rick Dichard encouraged him to take the course, and Plamondon says he’s glad he did.

Ditto all of that, says Josh James, also a senior.

“My savings account is more like a comfort, knowing I have money set aside for emergencies,” James says. He’s also started to focus more on saving than spending, and says he’s gained a deeper understanding of how loans work. Now he is less stressed about money.

“I learned to separate necessities and needs, like gas and groceries, and save money for the things I want, like a good pair of shoes,” he says.

He feels he can now contribute more to household expenses, including groceries, to avoid draining his paycheck on takeout, just like Plamondon.

“The course definitely changed the way I do things,” says James. “I would tell older people to take the course because it will help you in the long run. »

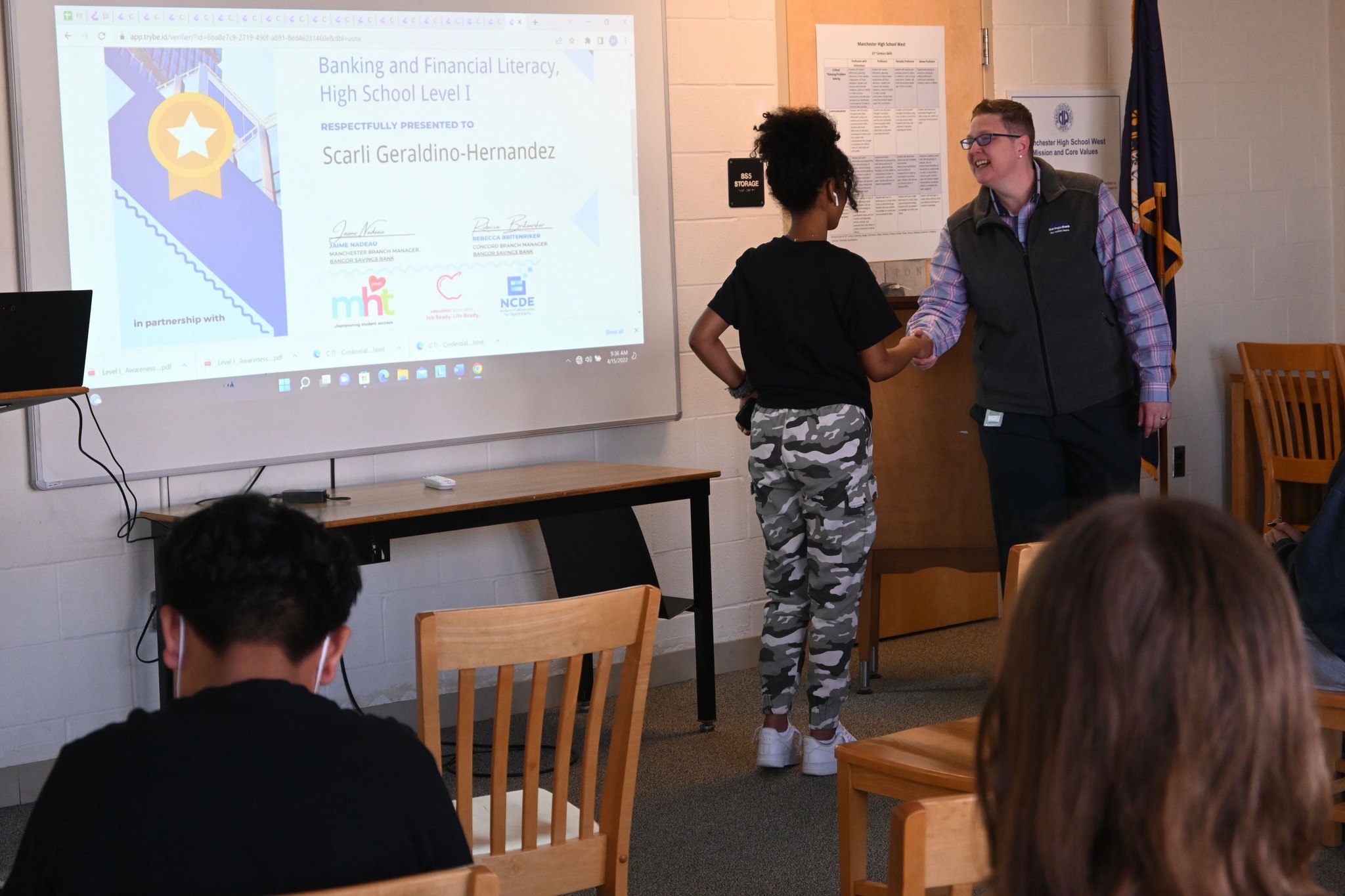

The Western Financial Education pilot program was taught by two bank managers from Bangor Savings Bank as a series of seven 90-minute lessons. Students who successfully completed the course received $25 to deposit into a newly opened bank account, an optional half-credit, and an industry-recognized digital badge, a kind of micro-certificate that has value as form of skill currency for future activities.

Plamondon and James both gave the program a 10 out of 10 rating and, they say, believe all students should take the course — a primary focus of the pilot program at West, Dichard says.

“School should really be a real preparation for life,” says Dichard. “We need algebra 1 but not financial literacy, and that’s something absolutely everyone in this world needs, so when those opportunities arise, we need to take advantage of them. I wish that was a graduation requirement. This is where we want to get to.

Dichard, a former math teacher, championed the program at West as chief cheerleader and chief student recruiter.

“That’s how I got the kids for this group and how random it was. We picked a time slot and looked at the kids who already had a study room so they were already ‘free. “, then we crossed our fingers that there was no snow day to alter our blue-white schedule. Then I went to these study halls and recruited, a child at the times,” explains Dichard.

Its incentives—giving all students who complete the course $25 to open a bank account and the chance to earn half-credit toward graduation—make the program a “no-brainer” classic. an expression he uses a lot around students.

“I like to tell kids that there are things in life that aren’t nonsense and this is one of them,” he says.

Of the 19 kids who signed up, 17 completed the course, and Dichard says they’re working with the other two students to get them to the finish line.

“The fact that not everyone has it tells you that we don’t hand it out like candy canes at Christmas. You have to complete it and pass a proficient test to get the credential, and now they all have a head start with these badges as part of their online digital wallet,” says Dichard. “It’s the wave of the future, with cryptocurrency and all that – cutting edge stuff, and that’s exactly what we want to be for our students.”

In addition to the financial literacy program, 10 students participated in a Digital Opportunity Leadership course, taught by Jenelle Leonard, a former program manager for the US Department of Education who is director of digital leadership development at NCDE. These students received a fully charged refurbished laptop which, at the end of the course, could be kept for personal use and to provide technical support to their peers, teachers and family members.

NCDE has worked with the district on other initiatives, including helping to bridge the “digital divide” that became evident at the onset of COVID-19.

At this time, Manchester Proud contacted the school district to identify the most important student needs, which was to get computers into the hands of low- and middle-income learners. Through a partnership with NCDE and Southern NH University’s School of Education, “Operation Lemonade” was launched. The initiative brought together a consortium of a dozen banks, credit unions and other funders in a Funding Partner Working Group, resulting in

- Distribution of 350 laptops to children in need across the city (funded by Bank of America, Bangor Savings Bank, Bar Harbor Bank, Bellwether Community Credit Union, Citizen’s Bank, People’s United Bank and Service Credit Union.)

- Bean Foundation funding to help families secure broadband through Comcast Internet Essentials.

- Coordinating workshops between the School District, Manchester Proud, NCDE, SNHU and NAACP, to promote seamless access and timely delivery of needed devices and services, using school social workers to identify students/families with needs

- In collaboration with VISTA and Victory Women of Vision, on creating an online program to train new, linguistically diverse American teens and young adults to provide technical support to students and families using laptops.

Mary Ford, director of Inclusive Pathways for NCDE, says there are other initiatives and resources for students and the community at large, such as BankOn New Hampshire, which helps the “unbanked” set up accounts with options free or low-cost verification checks with no fees or minimum balance required (click here for the current list).

“We found that many people were spending 20% of their income on check cashing fees because they didn’t have a relationship with a bank,” says Ford. This is especially common among New American families who arrive with little knowledge of the banking system or with a mistrust of institutions. “There are cultural differences at play, which is why this program was created.”

Not only does BankOn provide free financial literacy training, credit repair counseling and mentoring, but the larger goal is to strengthen pathways to paid careers and remove barriers to inclusion. financial and economic issues related to the digital divide.

Focusing on financial literacy education among West’s first cohort of students has been a testing ground for positive outcomes that provide lifelong lessons and help students transition into the future. college and career.

Dichard says that, like all pilot programs, the first pass provides insight and leads to improvements.

“The good part of the pilot is you learn. Most things went well and some things we learned,” he says. One of those lessons learned was that bringing in banking professionals to teaching high school students presents a challenge – for both.

“It’s not a college class. OWe teach secondary students and it is not an easy task these days so there must be help including more scaffolding for secondary students. You can’t just show a PowerPoint presentation and expect students to get what they need, so going forward we need to support our external partners with resources and be ready for the next cohort,” says Dichard. .

Due to the scope of the material, more time could be spent on the next iteration of the course, he says.

“We will work hard to redesign it and make it even better,” says Dichard. “It went well, and now it can be even more spectacular.”

He says he’s open to hosting another session this school year, if possible, but making the course a permanent part of the curriculum for all high school students in the district is a policy matter for the school board committee to decide.

“We’re going to do as many sessions as possible,” Dichard said. “All the kids would do this if it was up to me. Once we have another session under our belt, it’s time to make the case to the school board.”